Life in Nigeria has become a daily struggle for millions due to inflation, widespread poverty, and rampant government corruption in the country. With inflation hitting record highs and basic necessities becoming unaffordable, many Nigerians are feeling hopeless and abandoned.

In the thick of this growing crisis, the government has taken a hardline stance against public dissent. Once a powerful expression of public frustration, protests in Nigeria have now become tightly monitored, demonized, and in some cases, violently suppressed.

Despite the increasing difficulty in organizing mass movements, fresh protests have erupted in Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt under the banner of the Take-Back Movement.

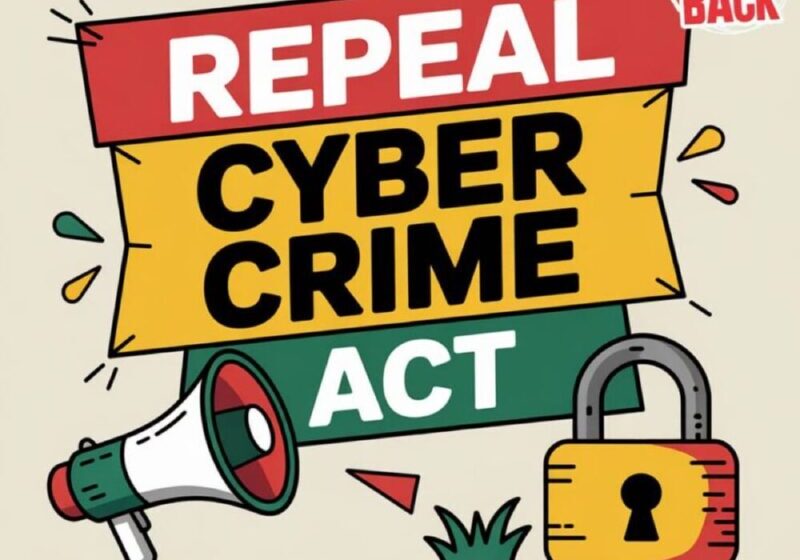

This latest wave of resistance is being led by former presidential candidate Omoyele Sowore. Sowore opined that this protest was organized as a response to widespread economic hardship and a stand against the increasing misuse of the Cybercrime (Prohibition, Prevention, etc) Act of 2015, which was amended in 2020.

A History of Resistance and Repression

Nigeria has a long and storied history of protests, often rooted in deep dissatisfaction with governance and the government’s failure to address citizens’ concerns. The tradition of resistance dates back to the pre-colonial era. And the gaining of independence did not end the need for protests. It rather intensified. Citizens have continually found themselves driven to the streets in response to systemic injustice and poor leadership.

Notable post-independence protests include the “Ali Must Go” student protests of 1978, the Anti-SAP riots in 1989, the June 12 pro-democracy protests in 1993, and the Occupy Nigeria movement in 2012. A review of these events shows a consistent pattern. Nigerians only rise en masse when hardship becomes unbearable and the injustice touches virtually everyone.

Interestingly, a recurring irony in Nigeria’s protest history is that those who ascend to power by leveraging public dissent often become intolerant of protests once in office.

For example, the 2012 protests against fuel subsidy removal saw politicians who had previously rallied against the former administration’s failings now suppressing the same methods of dissent they once embraced.

This betrayal not only worsened public mistrust, but it also reinforced a dangerous trend: leaders who exploit public grievances for political gain but clamp down on the right to protest once in power.

In recent years, government hostility toward protests has intensified. Milestone protests like EndSARS and EndBadGovernance, mobilized young Nigerians and civil society against police brutality and entrenched corruption. As expected, these protests were met with force, disinformation, and criminalization.

The Nigerian government resorted to treating protests as a crime akin to treason, rather than addressing the underlying issues that led to the protests. This has raised alarms both locally and internationally, as the space for civic expression continues to shrink in a country once known for its vibrant tradition of speaking truth to power.

The Rise of the Take-Back Movement

Several social commentators have noted that any future protests in Nigeria would likely have to emerge organically and without centralized leadership to evade government sabotage.

Today’s Take-Back Movement, while not entirely spontaneous, appears to lack the kind of structured coordination seen in previous protests. Demonstrators chanted their discontent using slogans that called for economic reform, accountability, and the restoration of civil liberties.

Citing the observance of National Police Day, the police dispersed protesters with tear gas and issued nationwide warnings against participation in any protest activities.

“This Is Just a Rehearsal”

Following the dispersal in Abuja, Omoyele Sowore addressed the crowd in defiance, declaring, “This is just a rehearsal. The real protests are coming, and the police won’t be able to stop them.” His words reflected a growing unrest among Nigerians, who are beginning to see the need to protest as the only way to set the country on the right path.

Despite police warnings, protesters still came out to voice their anger. This shows that the Take-Back Movement represents more than just anger. It is also a reflection of a country where a disenfranchised population is finding new ways to push back.

Conclusion

The Take-Back Movement is still in its early stages, and its success remains uncertain. Like past protests in Nigeria, it’s already facing heavy pushback. However, the message behind it is tied to the fact that Nigerians are tired of staying silent. People are fed up with poverty, government oppression, and deep-rooted injustice. Even if the protests slow down for now, the frustration is building. And the government may soon face a wave of resistance that no threats or crackdowns can stop.

For more about politics and governance, check out the Politics section on the homepage, and follow our socials @InsidesucessNigeria for more updates.

Leave a Reply